Efficient Error Handling Tips for Javascript Web Clients

Error handling in Javascript-based web clients is a fundamental constituting part of a web application. Poor error handling can sink your system before it even learns to float.

On the other hand, good error handling practices make things go swimmingly. This article discusses the best practices for a standard web application that communicates with a web server through standard HTTP calls.

Photo by Sarah Kilian on Unspash

Try Catch Blocks

Javascript on this subject is really similar to Java. It has the same syntactic statement used to catch and handle errors that occur in the try section. If you want to achieve efficiency in terms of code readability, simplicity, and usefulness, make sure to follow these rules when using try catch in your web application:

1. Don’t use try catch as a patch for a bad code.

“I don’t know what this code copied from Stackoverflow means. Let me wrap it up in a try catch block.” Try catching a block of code without knowing what errors it may throw is a bad practice that can result in a huge mess. Try catch should be used only when you know exactly what error you want to catch and handle.

2. Define fault barriers for every non-critical operation to increase robustness.

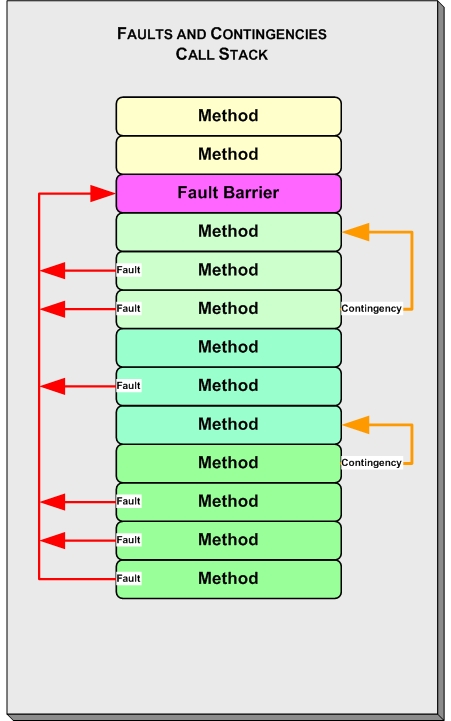

The concept of a fault barrier is very simple. It’s an abstract layer that resides logically toward the top of the call stack, where it stops the upward propagation of an exception so that the default action is not triggered.

Every web application (or system) consists of critical operations and non-critical operations. The failure of a critical operation is non-recoverable, while the failure of a non-critical operation is. Therefore, you should define a “fault barrier” so that any non-critical operation faliure can be recovered. It’s possible to implement fault barriers using try catch blocks, but you could also implement it using Promises.

applicationFlow() {

try {

notCriticalOperation_1()

}

catch ( e ) {

notCriticalOperationErrorHandler_1(e)

}

try {

notCriticalOperation_2()

}

catch ( e ) {

notCriticalOperationErrorHandler_2(e)

}

}

3. Do not try catch everything.

When defining a general exception handler, “try-catching” your entire javascript code is not recommended. If your scope is to log or monitor all the errors of your application, you should define an interceptor pattern instead (more on this pattern in the following section).

4. Do not suppress exceptions.

Javascript is a perfectly valid syntax to define a try block without a catch (). This is possible if, for example, you want to use the finally statement regardless of any exception on the code.

try {

doSomething(theData);

} finally {

doAnotherThing();

}

The doAnotherThing method will be invoked regardless of the result of the first method.

Of course, exceptions are there for a reason—to tell the user that something is wrong.

It’s a well-known software development “antipattern”

called “error hiding”. Information about the error is lost,

which makes it very hard to track down problems.

5. Not every exception should be logged.

Almost every experienced web developer has worked on a project with tons of error logging in the browser console. So much logging that reading is impossible. Try to log the useful information of the exception only. Consider that an exception is not handled and reaches the top of the software layers. This error will be written on the console.log. Writing it manually will result in a duplication of the lines.

Error Interceptor Pattern

The web application will usually communicate with a web server, which may respond with several different HTTP error codes. An efficient web application should react well in every situation.

A good way to proceed is to implement an interceptor pattern for every HTTP call and process the errors thrown by the web server in a centralized place.

If you are using React with Axios or Angular, it’s possible to define an interceptor that will process every HTTP call in a pretty straightforward manner.

It’s possible also to define an interceptor for Vanilla Javascript (example for the fetch method):

const constantMock = window.fetch;

window.fetch = function() {

// do something….

return constantMock.apply(this, arguments)

}

Say, for example, that we want to log out the user if an error code 401 happens. If it doesn’t happen, using an interceptor, we should write the code to handle this exception and redirect the user to the login page for each HTTP call. Thus, using interceptors, we can centralize this logic and avoid repetitions while also showing useful information to the user.

Another available option is to override the window.onerror function to implement an

interceptor for every exception that occurs on the client.

The onerror function is an event handler

that processes error events

fired at various targets for different kinds

of errors,

like runtime errors or resource loading errors.

Overriding is as easy as it can be:

window.onerror = function(message, file, line, column, error) {

window.alert("ERROR! example message ");

};

Handling Server Business Logic Error Codes

Business logic errors should be handled differently from other errors. Usually, these HTTP calls should respond with the 409 error code.

For this kind of error, it’s a good practice to share between the frontend and backend a well-defined list of exception codes for every application business error mimicking the BFF (Backend for Frontend) Pattern. In this way, it will be possible for the client to react accordingly, whether they need to show the correct error message or make another subsequent request.

fetch('https://example.com/profile', {

method: 'POST', // or 'PUT'

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

},

body: JSON.stringify(data),

})

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

console.log('Success:', data);

})

.catch((error) => {

if( error.status === 409 )

{

if(error.apiErrorCode === 100) {

showWarning('Profile already existing!!')

}

else if( error.apiErrorCode == 101) {

showWarning('Profile is not valid')

doAnotherHttpCall()

}

});

Error Logging and Monitoring

Logging errors in the web client console is useful to troubleshoot applications. In the test environment, it should be mandatory to log every exception to ease development.

However, in the production environment, the console and every developer tool should be disabled, which means there is no console to read from.

To remove console logging in the production environment, you just need to override the console.log function with an empty body function.

console.log = function () {};

In this case, to ease troubleshooting and be aware of eventual client errors, everything should be sent to an external monitoring application. We should rely, for example, on the interceptor of the previous chapter extending it to build a JSON object to send to an external server.

window.onerror = function(message, file, line, column, error) {

let data = {

type: error ? error.type : '',

message: message,

file: file,

line: line,

column: column,

stack: error ? error.stack : '',

userAgent: navigator.userAgent,

href: location.href

}

fetch('http://mymonitoringsystem:8080/log', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify(data) } )

}

fetch('http://mymonitoringsystem:8080/log', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify(data) }

Alternatively, if you don’t want to reinvent the wheel, you can make use of a third-party client-side logging service like SENTRY with its Raven.JS module. This automatically reports uncaught JavaScript exceptions triggered from a browser environment and provides a rich API for reporting your own errors.