Java Efficient Patterns for Exception Handling

Error handling is one of the most crucial parts of any application. In this article, which results from a lot of research and insights (and some experience in the field), we will see 4 peculiar patterns/best practices for handling errors or exceptions in Java.

Photo by Julian Bock on Unspash

1- Exception Wrapper Pattern

How: All exceptions thrown by methods in a peculiar package should be wrapped into peculiar exceptions.

When: This pattern is very useful if the code is to be shipped in the form of Java libraries, or if it includes several packages, all of which don’t have the same business logic. If your code is simple enough or does not provide any kind of libraries, using this pattern is not advisable as it will increase abstraction.

Why: Re-throwing exceptions will show implementation details to the client, which should be hidden. The client of the code should not be required to modify the catch cause for every update of the service code. Remember that the throw cause is part of the signature of the method, and any changes to the signature will impact the client. Say you have a large user-base for your package, this will result in a huge refactor.

Example: For their DAO support, Spring defines a consistent exception hierarchy hiding and wrapping low-level exceptions as Hibernate-specific exceptions, SQL Exceptions, etc.

Pattern Extensions: This pattern works by wrapping any exception in a specific runtime package exception. In this way, any boilerplate “try-catch“ code is removed. This pattern is very useful if no exception to the service package is recoverable (I recommend using checked exceptions only if the client can take some useful recovery action based on information in the exception. Otherwise the right choice is unchecked exceptions). The implementation is very simple and straightforward using lombok @SneakyThrows.

References:

- http://wiki.c2.com/?HomogenizeExceptions

- http://wiki.c2.com/?ConvertExceptions

- http://tutorials.jenkov.com/java-exception-handling/exception-wrapping.html

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/484794/wrapping-a-checked-exception-into-an-unchecked-exception-in-java

2- Fault Barrier Pattern

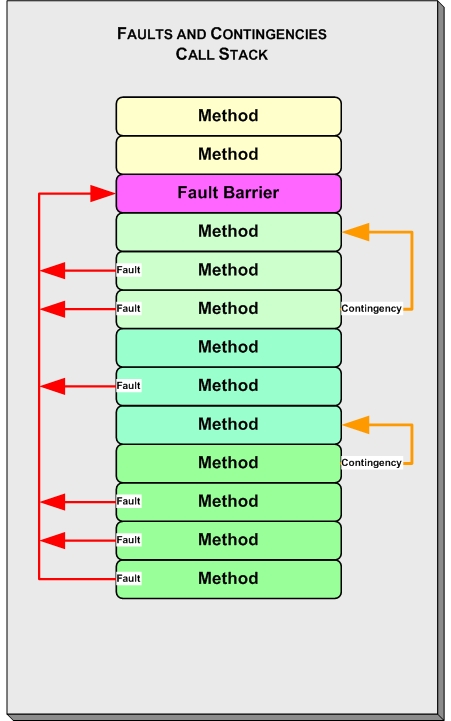

First, let’s start by defining two kinds of errors in Java. First, we have to distinguish between FAULTS and CONTINGENCIES.

- Faults are non-recoverable errors to be handled with unchecked exceptions.

- Contingencies are recoverable errors to be handled with checked exceptions.

The fault barrier pattern is a pattern that handles faults.

How: “In the fault barrier pattern, any application component can throw a fault exception, but only the component acting as the ‘fault barrier’ catches them.” Source. The fault barrier component should record the information contained in the fault exception for future action (logging) and close out the operation in a controlled manner.

When: You should follow this pattern in every application that can fail in some way. Practically speaking, you’ll want to use this pattern in every application.

Why: The fault barrier pattern enables the separation of concerns. It centralizes the logic of unwanted and unchecked errors (faults) in a single place. It also frees the business logic of your application from the burden of error handling and avoids the repetition of code.

Example: In the Spring Framework, it is possible to define a global exception handler component for the other methods, which will handle all faults using the @ControllerAdvice annotation.

import org.springframework.http.HttpStatus;

import org.springframework.http.ResponseEntity;

import org.springframework.web.servlet.mvc.method.annotation.ResponseEntityExceptionHandler;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.ControllerAdvice;

@ControllerAdvice

public class RestResponseEntityExceptionHandler

extends ResponseEntityExceptionHandler {

private static Logger LOGGER = LoggerFactory.getLogger(RestResponseEntityExceptionHandler.class);

@ExceptionHandler(value

= { IllegalArgumentException.class, IllegalStateException.class })

protected ResponseEntity<Object> handleConflict(

RuntimeException ex, WebRequest request) {

String bodyOfResponse = "This should be application specific";

LOGGER.error(“something happened”)

// we could also save the exception in a DB or send the datas to third party sw

return return new ResponseEntity<>(bodyOfResponse , HttpStatus.ERROR);

}

}With this simple code, we can handle both the exceptions—“IllegalArgumentException” and “IllegalStateException”—logging the error and providing an opportune HttpStatus to the client. Without this component, every detail about the error will be sent to the client, revealing implementation details that should be hidden. If you are using plain Java and not Spring, it is also possible to define a default uncaught exception handler, which is exposed by the “thread” java object.

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Thread.setDefaultUncaughtExceptionHandler(new ExceptionHandler());

}

class ExceptionHandler implements Thread.UncaughtExceptionHandler {

private static Logger LOGGER = LoggerFactory.getLogger(ExceptionHandler .class);

public void uncaughtException(Thread t, Throwable e) {

LOGGER.info("Unhandled exception caught!");

// handle the fault based on the class ( instanceof .. )

}

}Pattern Extensions: You don’t have to define global exception handler mechanisms only for faults. It’s possible to define them for checked exceptions too. In fact, along with the example provided in the previous paragraph, it is advised to define a standard HTTP code and a log for every exception handled by our rest controllers.

References

- https://www.oracle.com/technical-resources/articles/enterprise-architecture/effective-exceptions-part2.html

- https://www.baeldung.com/java-global-exception-handler

- https://www.baeldung.com/exception-handling-for-rest-with-spring#controlleradvice

3- Exception Bouncer Pattern

This pattern should also be called the “Validator Pattern”. It is a way of implementing the beans validations using exceptions, which is the best way of doing it, in my opinion.

How: It defines methods that just throw exceptions based on validations.

When: It can be used in any application that needs input validation. Basically, every time.

Why: There are several ways of doing input validation in Java. You should, for example, return a boolean that checks for validations. Exceptions are a good way to go because you can provide an insightful message inside them and distinguish among different kinds of input errors. Additionally, throwing exceptions to the upper layer means freeing the application from the logic of handling exceptions, and avoiding repetitions.

Example:The most basic example in Vanilla Java is simply to define a method, called before the business logic act, that just validates input and throws exceptions.

public boolean checkInput(SomeBean bean) {

if(bean == null ){

throw new IllegalArgumentException("The bean is null");

}

if(bean.getName() == null ){

throw new IllegalArgumentException("the name is null")

}

}More advanced validation is done in the Spring Framework, where you can use the @Valid annotation on your request body POST object instead.

@PostMapping(value = "/endpoint", consumes = "application/json")

public ResponseEntity<Object> endpoint(

@RequestBody @Valid SomeBean dto)At this point, the SomeBean should be annotated with JavaX package annotations. If the validation as specified by the annotations is not achieved, a bouncer method will throw a JavaX validation exception.

import javax.validation.constraints.Size;

import javax.validation.constraints.NotNull;

@Getter @Setter

public class SomeBean{

@NotNull

private Integer someField;

@NotNull

@Size(max = 10, min=0)

private Integer someField2;

}This exception can also be refined and enriched with opportune details and well logged and monitored if you apply the fault barrier pattern mentioned earlier in this article.

References

4- Error Code Pattern

How: It gives a specific code number for each checked exception.

When: It can be used in any Java project that uses checked exceptions as business errors.

Why: Giving a number/code for each different exception message is a good practice for documentation and faster communication. In addition, it’s easy to hide information that can otherwise be exposed to clients.

Example: Suppose you have a REST method that saves a book object into the database. To save this book object, some constraints have to be validated, like:

- the ISDN code should be valid

- the author of the book must already be saved into the database

- the book name should be a string of size 1

You can simply handle these validation errors using exception messages and the same HTTP error code. Additionally, please consider using the HTTP error code accordingly for web applications. In this case, for example, the HTTP error code should be 409 as it is the standard way to report business errors.

Or you can use the more efficient error code pattern. Using this pattern, you can give a specific number to each exception and share with trusted clients what the code means.

if( !checkValid(bean.getIsdn()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(ErrorCodes.IDSN_CODE_NOT_VALID)

}

public final class ErrorCodes {

// ...

public static final STring IDSN_CODE_NOT_VALID = “00001311”

}In this way, the exception thrown will HIDE any insightful information about the issue. In a BFF (backend for frontend), this is the best way to handle error codes. The client should know that the error with the code “00001311” has a specific meaning. We can also use the fault barrier together with this pattern, giving numbers to exceptions based on classes:

@ExceptionHandler(value = { BookIsdnError.class })

protected ResponseEntity<Object> handleConflict(RuntimeException ex, WebRequest request) {

String bodyOfResponse = ErrorCodes.IDSN_CODE_NOT_VALID;

LOGGER.error(“BookIdsError”, ex)

// we could also save the exception in a DB or send the datas to third party sw

return return new ResponseEntity<>(bodyOfResponse , HttpStatus.ERROR);

}In this way, we will still have the application logic regarding exceptions centralized in a single place where they are easy to locate and edit.